"Why I Gave Up My Breasts"

As told to Andrea Buchanan

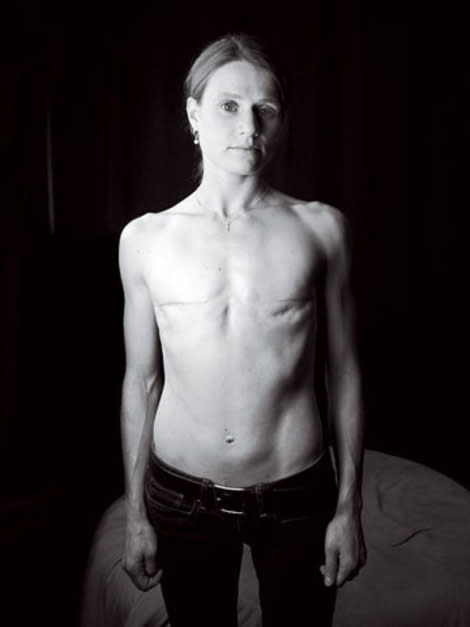

When Margaret W. Smith -- mother, wife, soldier, and marathoner -- had a double mastectomy at age 29 as a preemptive strike against cancer, she chose not to reconstruct. She says it was the smartest decision she ever made.

Related: How to Do a Breast Self-Exam

Margaret's Story

I always had big boobs. I would wear two sports bras and my breasts would still bounce when I ran.

That changed on June 2, 2009. I walked into the army's Walter Reed Medical Center with D cups that morning; by afternoon I was flat chested, wrapped in gauze and sobbing. The loss was tremendous. But mostly I felt overwhelming relief; a physical and emotional burden had been lifted.

For 17 years I'd been carrying around breast cancer baggage. My experience with the disease began in sixth grade. While other kids were snickering at the word boobs, I had to face the harsh reality that my mother had lost one of hers. I would get so embarrassed whenever I spotted her on the sidelines at my soccer games, her prosthetic breast floating all over her chest as she cheered me on. It was 1992, the year the pink ribbon became popular and breast cancer was coming to the forefront of social consciousness. But for me, the disease was the bully I could never really shake. About nine years later it came back full force, taking my mother's other breast and, eventually, the life of her sister, my Aunt Christine.

It seemed to run in the family, and, indeed, my mother tested positive for the hereditary BRCA2 gene mutation, which puts a woman's chance of getting breast cancer at as high as 80 percent, and ovarian cancer at 15 to 40 percent. Her results meant I had a fifty-fifty chance of having the mutation too. If I did, I would be faced with the decision of whether to have both of my breasts surgically removed to drastically diminish the scary odds or to take my chances and hope I didn't get the disease.

Related: The Who-Knew Facts About Your Breasts

At the time we learned that my mom had the BRCA mutation, I was 25 years old and about to be deployed to Iraq. Overseas duty prevented me from getting the gene test done right away. In fact, four years passed, during which I met and married my husband, Patrick, and we had our daughter, Emily, now 4. Those years were rough, though. Not only was I constantly playing the "what ifs" in my head, but I also had a severe case of postpartum depression after Emmie was born. I'm not proud to admit that I turned to alcohol in order to cope. It was a dark and familiar place: I'd spent the early part of my twenties, during my mother's illness and my aunt's death, in a self-induced haze.

When I finally got tested and learned that I did have the same gene mutation, something in me just clicked. I knew I needed to take control of my health and my life; I had to be there for my daughter, and living with the threat of cancer was no longer an option. A month later I had the double mastectomy. It was a very difficult decision but one that I had already been grappling with for years.

When you choose to have this surgery, the first thing doctors mention is setting you up with a plastic surgeon for reconstruction. It's practically unheard of for a woman at my age to say "No, I don't want it." I had seen my mom cope really well without reconstruction, and in a lot of ways I admired her for that. Meanwhile, my Aunt Chris had had an awful time with an infection after reconstruction.

Mostly, though, I thought about how it would affect my daughter. After a mastectomy, you can't pick up anything heavier than a gallon of milk for a month. If I had chosen reconstruction as well, I wouldn't have been able to get on the floor and play with Emmie for nearly a year without worrying about her bumping my chest. I didn't want to miss that precious time with her. I might have had the reconstruction if it had been important to Patrick, but luckily it wasn't. He said, "I love you for you, not your breasts."

Related: Your Guide to Healthy Breasts: What Those Weird Lumps and Bumps Really Mean

The fact that I'm a runner also helped seal the deal and gave me the strength to say good-bye to my breasts for good. I appreciated them for their obvious charms, but in all honesty, because I'm a petite person, I had always felt as if they belonged to somebody else. And, seriously, I hated all that bouncing.

Running helped me through my recovery. I started jogging two weeks after surgery. It was a bit weird at first because I had lost six pounds in upper-body weight and that threw my balance off, but I got my legs under me quickly and felt great. I loved going without double sports bras; it was as if I had been set free!

I ran the 2009 Marine Corps Marathon just four months after my surgery and qualified for the Boston Marathon, which I ran the following spring. Proving that my body is powerful and awesome really boosts my confidence.

Still, there are times when I'm shopping for dresses and I think, Things would be so much easier if I had gotten small implants. But those moments are rare, and I don't regret my decision. Taking action against the gene for the sake of my health has been the most empowering thing I've ever done. I'm a better mom, wife and person now. These days I've been working with FORCE [Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered; facingourrisk.org], a "previvor" group for those affected by hereditary breast and ovarian cancer, and I share my story with women who are facing double mastectomies and deciding whether or not to reconstruct. Last year, through the organization, I also had the opportunity to appear topless as a body double in the Lifetime movie Five, about breast cancer. I'm glad I did it, because I want women to see the real thing. I want them to know: Womanhood isn't defined by your breasts.

More from FITNESS Magazine:

Beat Your Period for Good

4 Foods That Fight Breast Cancer

The Big Issue with Breast Cancer: How Your Weight Affects Your Risk